Foreign Policy (March 2021) — “Why Lebanon Can’t Kick Its Addiction to Indentured Labor”

Photo: Abby Sewell

Marwan Hamadeh, a 27-year-old Lebanese man, has a secret life. Five days a week, he cleans offices around Beirut. “From my family, nobody knows,” said Hamadeh (who has asked to use a pseudonym) in March. “The idea wouldn’t sit well with them.”

It was out of desperation that Hamadeh turned to cleaning. Once a mobile phone repairman, Hamadeh lost his job in Lebanon’s jaw-dropping economic crisis, which erupted in October 2019 and has since slashed the Lebanese lira’s value by 90 percent. Last August, laden with debt and financially responsible for his parents, Hamadeh needed to find other work. His predicament is common among Lebanese; his response is anything but.

Of the 40-strong staff at the cleaning company he works for, Velvet Services, Hamadeh is the only Lebanese among mostly Bangladeshis. “Honestly, I know [Lebanese] people who really need work, but none of them work as cleaners,” Hamadeh said. “I know that they wouldn’t do this kind of work.”

Nivine Zarzour, Hamadeh’s boss, has tried to hire more Lebanese, whom she can pay with lira instead of increasingly scarce—and expensive—U.S. dollars. But she has failed to attract Lebanese recruits, which she traces to a deep-seated cultural stigma. “The main reason is not the salary,” Zarzour said. “We [Lebanese] always had foreign cleaners and helpers.”

For decades, Lebanon has relied on migrant workers—recruited from such countries as Bangladesh, Ethiopia, and the Philippines—to clean houses, operate gas pumps, and stock supermarket shelves. The largest sector for migrant labor is live-in domestic work, which accounted for 80 percent of migrant labor permits issued last year, according to statistics obtained from the Ministry of Labor.

Demand for foreign workers has propped up Lebanon’s notorious kafala system, which activists decry as exposing workers to modern-day indentured servitude. Originating in the Gulf, kafala ties a migrant worker’s residency in Lebanon to their employer, or kafeel(sponsor). Kafala workers rarely enjoy basic guarantees of rest days, set working hours, or freedom to switch jobs …

Click here to read the full article.

Foreign Policy (December 2020) — “Lebanon’s Concrete Cartel”

Photo: Joseph Eid / AFP

Even after decades, the international community still has not quite figured out what makes Lebanese politicians tick. Potential donors focus on economic mismanagement and political will, but gloss over the shady commercial interests that keep sectarian leaders popular.

When Saad Hariri, one of Lebanon’s most controversial politician-businessmen, returned to the position of prime minister in October—one year after protests forced his government to resign—it signaled a depressing return to business as usual.

Like outgoing U.S. President Donald Trump, Hariri inherited a business empire from his real-estate tycoon father and is not afraid of mixing business and politics. Also like Trump, Hariri and Lebanon’s other sectarian leaders enjoy supporter bases of Trumpian fervor. He’s not alone. Since the Lebanese civil war, the country’s leaders have fused politics and commerce, abusing their positions to buy their supporters’ loyalty. Business cartels with political connections leech off government subsidies, filch lucrative state assets, and wildly overcharge for basic products and services. Rank-and-file loyalists also benefit from corrupt patronage networks, financially tying even more constituents to their leaders …

Click here to read the full article.

New African (June 2019) — “Cover Story: Can Bitter Past Signpost a Better Future?”

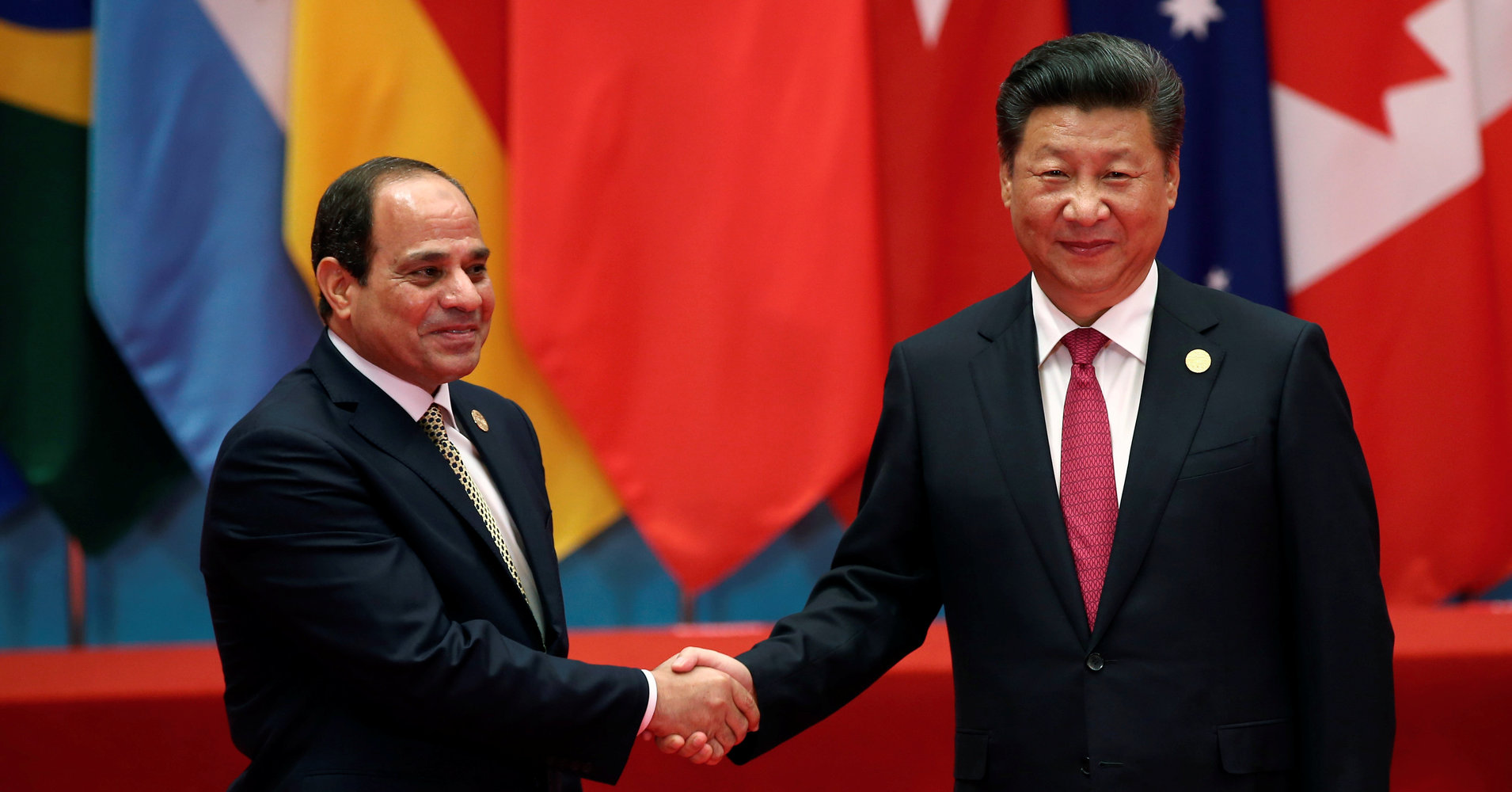

Foreign Policy (28 Aug 2018) — “Egypt Loves China’s Deep Pockets”

Photo: Damir Sagolj (Reuters)

Gamal Abdel Nasser, former president of Egypt and Cold War schemer, was not averse to playing hardball with powerful countries. In 1955, Nasser grew tired of dallying from Washington on a long-stalled arms deal. He shocked the West by approaching the Soviet Union, buying military equipment through Czechoslovakia, and igniting fears of a Middle Eastern arms race.

Six decades later, Cairo is looking for the best political bargain it can get once again, making diplomatic overtures to Moscow and Beijing while maintaining its crucial U.S. and Persian Gulf backers.

As under Nasser, the Egyptian leadership has become frustrated with the United States. The relationship grew frosty during the presidency of Barack Obama, who refused to invite President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to Washington amid accusations of human rights violations. Sisi has since made a state visit to Donald Trump’s White House, but the administration’s long-term Egypt strategy remains unclear.

Congress has complained about a perceived lack of benefit for the United States from the billions it has provided to Cairo over decades. It denied almost $100 million in military aid last August, citing concerns about a repressive new law restricting nongovernmental organizations’ work.

These tensions have created new openings for both Russia and China. Moscow responded to the Sisi-Obama impasse by entering into eyebrow-raising military cooperation accords and large-scale arms deals with Cairo. With less fanfare, Chinese money is increasingly pouring into the Egyptian economy, suggesting that the “comprehensive strategic partnership” agreed between the countries in 2014 could now develop some real teeth.

Egyptian-Russian relations have developed a stronger military tint under Sisi, the former field marshal who led the July 2013 overthrow of Egypt’s first democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi. The two started holding joint naval and military exercises in June 2015. Reports circulated in late 2017 that the two countries were negotiating an agreement for reciprocal use of each other’s air force bases.

Sisi has also lent a welcome source of Arab support to some of Putin’s dicier foreign-policy exploits in the Middle East. Cairo has given diplomatic cover to Russia’s backing of the beleaguered dictator Bashar al-Assad in Syria and allegedly provided a base for Russian troops to reinforce the maverick, anti-Islamist commander Khalifa Haftar in Libya.

At times, the Sisi regime has actively snubbed its long-standing allies in pursuing closer ties with the Russian military establishment. Egypt infuriated Saudi Arabia in October 2016 by voting in favor of draft United Nations Security Council resolution on Syria that was drafted by Moscow and opposed by Riyadh. This May, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov praised Egypt for rebuffing a U.S. request to deploy soldiers to Syria.

Egypt’s reward has been the series of Russian arms sales, which Mordechai Chaziza, a political science specialist at Israel’s Ashkelon Academic College, argues have become crucial to Cairo’s Moscow strategy. As the United States has shown a greater reluctance to provide military aid, the Kremlin has stepped into the void. Russia signed a $3.5 billion weapons deal with Egypt back in 2014, and it delivered more than $1 billion worth of military equipment last year alone.

Economic ties have also grown. Russia and Egypt pledged to develop a “Russian industrial zone” at the Suez Canal, where the plan is for a glut of investment from Russia on favorable terms. During Putin’s state visit to Cairo last year, Russia agreed to finance and oversee the construction of a $21 billion nuclear power plant near El Alamein. The project remains at a very early stage, but the Egyptian government predicts that the facility will begin operating from 2026.

Despite these grand designs, Russia’s strained finances limit its ability to wield decisive economic influence in Egypt. Timothy Kaldas, a nonresident fellow at the Tahrir Institute for Middle East Policy, argues that any attempt to chasten the United States by reaching out to Putin has failed.

“The Egyptians wildly overestimated how irritating that might seem,” he said. “The Americans know that Russia cannot replace them or the Gulf … because [Russia] is [effectively] broke.”

One nation that is far from broke is China, whose economic importance to Egypt far outweighs Russia’s. Beijing has been Cairo’s largest trade partner since 2012, with China providing 13 percent of total import value last year alone—almost double that of Germany, the next highest exporter to Egypt.

The Sisi administration has capitalized on Egypt’s strategic location as a key incentive for closer Chinese relations. “The Suez Canal is what makes Egypt exceptional [to China],” said John Chen, an expert in Sino-Middle Eastern relations at Columbia University …

Click here to read the full article.